As we leave the first quarter of the twenty-first century behind, the picture painted by global developments is crystal clear: In the coming era, minerals will be at the forefront of the power elements shaping the world’s political and economic balances.

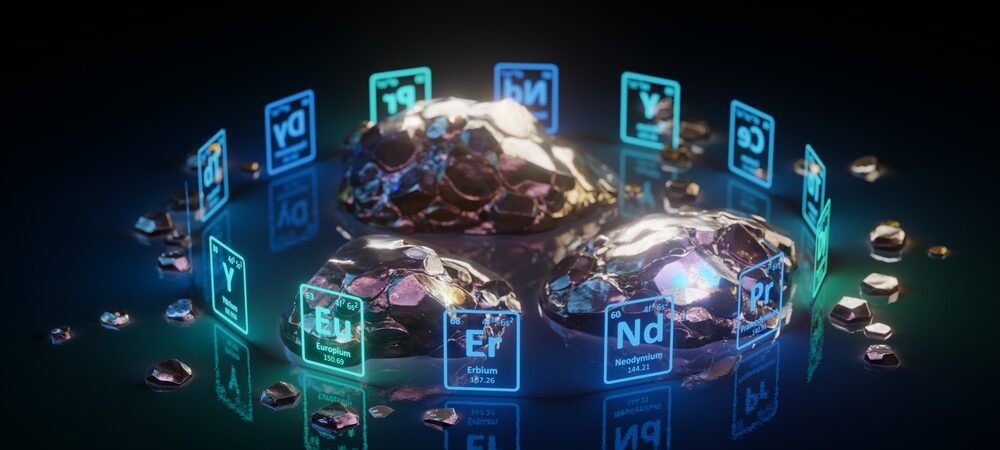

The primary driving force behind this development is the global energy transition process initiated to combat climate change. Worldwide, there is a massive and continuous surge in demand for critical minerals, which are indispensable for the transition to green energy and the interconnected digitalization processes. According to the International Energy Agency, the mineral demand required by clean energy technologies to achieve the Paris Agreement goals will quadruple over the next 15 years. (1)

On the other hand, it is estimated that the global urban population will more than double by 2050, triggering a massive demand for raw materials to construct urban infrastructure. Consequently, humanity will need to extract more mineral ore from the depths of the earth in the next 30 years than it has produced in the last 70,000 years.

The Struggle for Control Over Critical Minerals

Given this context, the conviction that those who control critical minerals will shape the global economy in the coming years is gaining momentum. As the mining sector rises to global prominence, we observe that control over the reserves and production of critical minerals—much like in the case of fossil fuels—is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few nations or corporations. Furthermore, the fact that the powers dominant in fossil fuels also control critical mineral deposits enables them to steer energy transition processes in alignment with their own interests. These actors, through their capacity to slow down or completely halt mineral supply at will, possess the power to dictate global prices. This extreme concentration of resources creates severe vulnerabilities in global supply chains, leaving many resource-dependent nations strategically defenseless.

On the other hand, countries hosting critical resources—such as cobalt, copper, lithium, nickel, graphite, and rare earth elements—are well aware that the treasures they hold are becoming increasingly valuable. Those in possession of these resources have already begun dreaming of becoming the ‘OPEC of the new era.’ Many of these nations, still haunted by the grim memories of the colonial era, now desire to extract—this time—greater value from their mineral wealth to fuel their own national development. They no longer wish to be viewed merely as ‘raw material warehouses’; they intend to process the minerals within their own borders and industrialize.

Resource Nationalism or Strategic Choice?

However, this preference is often labeled as ‘resource nationalism’ through an exaggerated, predominantly Western-centric generalization; a label further embellished with the stigma of being an ‘atavistic form of protectionism’ and the claim that it poses an obstacle to overcoming the climate crisis. Yet, the reflex to protect critical and strategic resources—for which demand is rapidly surging—cannot be explained by romantic nationalism or a mere ideological stance. Ultimately, this choice is a matter of realpolitik and political economy, driven by a pursuit of national interests that can be justified by even the simplest economic calculations.

Although I find it flawed and confusing, this term remains in use. Moreover, a ‘Resource Nationalism Index’ is systematically calculated to measure the level of state control over mining activities. (2) The picture presented by this index is quite striking: the increasing strategic importance of minerals has not benefited free trade; on the contrary, it has triggered a new wave of protectionism worldwide.

In this new era, many countries are now placing their mineral resources under protection while raising tax rates, imposing bans on the export of raw or concentrated ores, and mandating the establishment of local facilities to transform ore into high-value-added products. Requirements such as domestic partnership or local labor quotas for foreign companies are also being implemented. It appears that countries—realizing that mining revenues are leaking abroad without providing significant domestic benefits—are striving to exert greater control over their mineral wealth.

The Era of Protectionism in Mining

There are numerous recent examples of this emerging trend: In early 2022, Mexican President López Obrador initiated a comprehensive lithium nationalization program by enacting revolutionary changes to the mining law. (3) Subsequently, a similar move came from Chile, which has long been a favorite of international mining corporations. In April 2023, President Gabriel Boric announced a plan to nationalize the lithium industry, declaring that new contracts would henceforth be conducted solely through state-controlled public-private partnerships. (4) Furthermore, the Chilean government is pursuing a regional lithium alliance with neighboring Argentina and Bolivia, which together form the ‘Lithium Triangle’—home to 65 percent of the world’s lithium reserves.

Indonesia, which supplies more than half of the world’s refined nickel, took a radical step in 2020 by completely banning the export of this ore, mandating that all nickel be processed in domestic facilities. Clear objectives were set behind this strategic move: to shift from being a mere raw material supplier to capturing the added value within the supply chain for the Indonesian economy, strengthening local businesses, creating new jobs, and stimulating economic development. (5) With this policy, Indonesia transformed the mode of value creation in the local nickel industry, resulting in a boom in domestic processing capacity. Global investors, particularly from China and Germany, were forced to relocate their technology and capital to Indonesia to establish high-tech processing plants. Consequently, Indonesia is no longer just the owner of the ore; it now controls more than half of the global refined nickel market. (6)

The wind of protectionism has also swept across the African continent. Zimbabwe, which banned the export of raw lithium in 2022, expanded this restriction to cover all base minerals at the beginning of 2023. Furthermore, it plans to ban the export of lithium concentrates starting from 2027. (7) The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), home to some of the world’s richest cobalt, copper, and other critical mineral deposits, implemented significant increases in royalties and tax revenues by amending its mining legislation in March 2018. (8) Today, the DRC is reopening existing mining contracts for renegotiation in line with ‘national interests.’ A similar strategic move came from Namibia. In accordance with its ‘Mineral Beneficiation Strategy’ announced in 2021, Namibia declared a ban on the export of critical minerals such as raw lithium ore, cobalt, manganese, graphite, and rare earth elements in June 2023. (9)

Protectionist Policies Are Not Exclusive to Developing Nations

Examples are numerous. In a vast geography stretching from Kazakhstan to Brazil, and Algeria to Bolivia, many countries are taking consecutive measures to secure a larger share of their underground wealth. However, the ‘mining wars’ are not limited to resource-rich nations. The advanced economies of the ‘West,’ which are dependent on these resources and concerned about supply security, have also been caught in a wind of state interventionism and protectionism not seen since the first half of the 20th century. Moreover, major economies such as the US, Germany, Spain, the UK, and Poland are among the pioneers of this new wave of protectionism. Seeking particularly to break the dominance of China and Russia in critical mineral chains, these countries are using state power to subsidize key industries while blocking or limiting the investments of their competitors in strategic sectors.

On one side, China is playing its ‘raw material card’ by imposing export restrictions on the critical resources it holds; on the other, Washington is stockpiling strategic minerals, incentivizing domestic mining, and attempting to break its dependence on Chinese resources by bringing alternatives like Greenland and Ukraine to the table. To secure access to critical minerals, it is striving to build a vast ‘supply bloc’ stretching from Australia to Canada and Japan, and from India to the European Union. (10) This wave of protectionism is also manifesting as foreign investment restrictions in Canada and Australia—long considered bastions of the free market—where existing rules are being tightened daily through new regulations. While the goal is to keep resources under the control of ‘allied nations,’ a new ‘Iron Curtain’ is being drawn against market entry from the outside through the imposition of stringent environmental and labor standards.

Meanwhile, Germany has emerged as one of the lead actors of protectionist policies in the new era triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Having seized Russian energy assets following the war, Berlin is pushing incentive mechanisms to their limits to increase mineral processing capacity, aiming to support the green transition and fortify energy security. (11) Today, the security of critical mineral supplies has become one of the fundamental pillars of German industrial strategy. Through strategic partnerships established with resource-rich nations, Berlin is seeking guaranteed access to a wide spectrum of materials, from lithium to rare earth elements. It appears that when it comes to ‘national security’ or ‘energy security,’ liberal market principles are nothing more than mere details for Europe.

As the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy sources accelerates and global mineral demand rises in tandem, it is no prophecy to foresee the emergence of new dependency relationships and strategic blocs. On the other hand, as protectionist measures tighten and supply security risks escalate, the accumulation of tension between resource-rich nations and those increasingly desperate for these minerals will inevitably lead to conflict.

To read the analysis as it was posted on Eurasia Review : Click Here