China’s construction of a nationwide “social credit system” has been identified as a major concern by both the executive branch and some Members of Congress because of the broad controls such a system is likely to give the Chinese government over U.S. citizens and companies operating in China. Recent reports of Chinese officials invoking the social credit system to pressure U.S. firms to take positions that align with Beijing’s interests raise questions for Congress about how to respond to the potential threat the system may pose to U.S. commercial actors in China.

After several pilot programs, China began constructing a nationwide social credit system in 2014, guided by a document issued by China’s cabinet, the State Council, Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014-2020). The plan describes the system as necessary to build “trust” in the marketplace and broader society, and establishes a 2020 implementation deadline. Since the plan was published, the social credit system has developed into two connected but distinct systems: a system for monitoring individual behavior, still in early pilot stages, and a more robust system for monitoring corporate behavior: the Corporate Social Credit System (SCS).

What is China’s Corporate Social Credit System?

The Corporate SCS is currently a network of initiatives operated by state and private actors at the national and local levels, connected by shared data platforms and a common goal of regulating corporate behavior in the Chinese market. The network’s overarching structure consists of three components:

Data Aggregation. A firm’s social credit profile is the aggregate of potentially hundreds of data points compiled by dozens of government entities. In October 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s powerful economic planning agency, launched the National Credit Information Sharing Platform (NCISP). The NCISP, operated by the NDRC in cooperation with 45 other government ministries, serves as the data “backbone” of the Corporate SCS, integrating all national and locallevel corporate regulatory data. To structure the database, all companies registered in China have been assigned a Unified Social Credit Code—a common identifier used across all datasets linked to the Corporate SCS.

Evaluation. As government departments collect information on firms, they create “blacklists” of firms that are found to have violated regulations or engaged in illicit financial behavior. National and local government departments have a wide mandate to create blacklists for violations that fall under their jurisdiction. Consequently, there are hundreds of official blacklists covering everything from severe offenses, such as tax evasion and falsifying emissions data, to minor offenses such as failing to file a change of address. Some departments also publish laudatory “redlists” of firms with exemplary records, such as the State Taxation Administration (STA) “Grade A Taxpayer List.” The National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System (NECIPS), a public online database run by the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), records each time a firm is added to or removed from a blacklist or redlist. Firms placed on multiple blacklists or that commit particularly serious offenses can be added to SAMR’s forthcoming “heavily distrusted entities list”—the closest analogue to a national blacklist.

Joint System of Punishments and Rewards. The primary enforcement mechanism of the Corporate SCS is a “joint system of punishments and rewards,” a set of legal cooperation agreements by which government agencies enforce each other’s blacklists. Under this framework, a firm blacklisted by the STA for tax offenses can be subject to customs penalties and more frequent financial audits based on cooperation agreements between the STA and China’s customs and financial authorities. Firms on the STA’s “Grade A Taxpayer” redlist, on the other hand, are not only eligible for expedited and less costly tax filings, but are also eligible for other benefits, such as customs fee waivers and low-interest loans. The system is designed, in the words of President Xi Jinping, “to make everything convenient for the trustworthy, and ensure the untrustworthy cannot move a single step.”

How is the System Being Implemented?

Although much remains to be done and data sharing gaps persist, reports indicate that China’s Corporate SCS is moving beyond its pilot stages and is on track for at least partial implementation in 2020. Many laws passed and regulations issued since 2014 include clauses stating that non-compliance will be recorded in the Corporate SCS. In July 2019, the State Council issued Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Building of the Social Credit System, which urges government agencies to “fully employ next-generation information technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence to achieve comprehensive credit monitoring.”

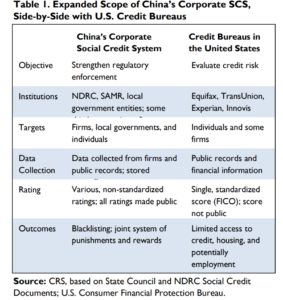

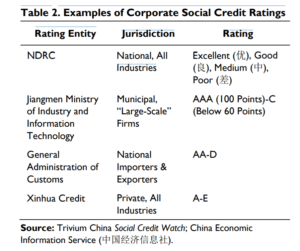

China’s central government has only issued general guidelines for the buildout of the Corporate SCS. Consequently, no single standardized national social credit score is currently assigned to companies. Instead, various national and local government entities, as well as some third party companies, are issuing their own social credit ratings to firms based on NCISP and NECIPS records (Table 1). In September 2019, the NDRC announced it had completed its first “social credit evaluation” of 33 million domestic Chinese firms and assigned each of them a “Comprehensive Public Credit Rating.” This NDRC rating is the closest analogue to a national corporate social credit rating, but government documents indicate that it will only serve as a baseline for corporate social credit evaluation and will not take precedence over local or sector specific ratings.

Multinational firms are already subject to the system’s data reporting requirements, according to the U.S.-China Business Council and the EU Chamber of Commerce. Some are already being rated by third-party companies authorized to issue corporate social credit reports: one such company, Xinhua Credit, launched an English-language version of its web portal in September 2019, providing one of the first platforms for non-Chinese firms to access corporate social credit data.

Policy Implications

New Government Market Access Controls. Chinese officials and some international observers contend that the Corporate SCS may create a more level playing field by merging domestic and multinational firms into a single, nominally more transparent regulatory regime. Certain provisions and rating criteria, however, could be used to discriminate against multinational firms, including for political purposes. For example, the Civil Aviation Administration of China pressured multiple international airlines in early 2018 to change their websites’ descriptions of Taiwan, stating that failure to comply would be recorded in each airline’s social credit records. Additionally, SAMR’s “heavily distrusted entities list” includes provisions that might be used to target U.S. firms. The list will include, for example, firms that “threaten national and public interest” or “infringe on the rights and interests of consumers.” Two U.S. companies—FedEx and Flex Ltd.— were accused of the latter, following supply disputes with Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei in mid-2019.

The NCISP also includes political data that tracks the number of Communist Party members employed by firms; firms that hire fewer Party members or avoid Party building activities may be penalized under the Corporate SCS framework. The Corporate SCS may also lead to a more opaque market access regime and increase compliance costs for U.S. firms operating in China. A recent report on the Corporate SCS published by the EU Chamber of Commerce estimates that multinational firms in China will be subject to approximately 30 different ratings under the Corporate SCS, the requirements of which will be dispersed across numerous government documents. Firms are also required to disclose to the Chinese government detailed data and other information about their operations and capabilities, including IP data related to patents and copyrights.

Expansion of China’s Economic Influence. The State Council’s 2014 Planning Outline explicitly identifies the Corporate SCS as a means of “enhancing China’s soft power and international influence.” To that end, Beijing has framed “credit cooperation” as a central component of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and is working to export the Corporate SCS more broadly. Several countries in Asia and the Middle East participating in the BRI have engaged in credit cooperation initiatives organized by the NDRC. Saudi Arabia, a strategic U.S. partner, is constructing its own Corporate SCS as part of its BRI cooperation with China. If the Corporate SCS is exported more broadly along the BRI, the Chinese government could potentially monitor and influence the behavior of U.S. firms and their interactions with Chinese companies in global markets, even if they are not directly operating in China.

Select Legislation in the 116th Congress

In the 116th Congress, the UIGHUR Act of 2019 (H.R. 1025) includes a provision that requires the Department of State to submit a report to Congress detailing the social credit system’s potential impact on the geopolitical and economic interests of the United States. Additionally, the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2018 (H.R. 3289 and S. 1838), in its current form, requires the Department of Commerce to conduct an assessment of whether dual-use items subject to U.S. export control laws are being used to develop China’s social credit system.

CRS China Social Credit SystemTo read original report, click here