Overview

The World Trade Organization (WTO) was established on January 1, 1995, following the ratification of the Uruguay Round Agreements and today includes 164 members. It succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was created in 1947 as part of the postWWII effort to build a stable, open international economic framework. The WTO has three basic functions: (1) administers existing agreements; (2) serves as a negotiating forum for new trade liberalization; and (3) provides a mechanism to settle trade disputes among the parties. The multiple WTO Agreements cover trade in goods, services, and agriculture; remove tariff and nontariff barriers; and establish rules on government practices that directly relate to trade—for example, trade remedies, technical barriers to trade, customs valuation, intellectual property rights, and government procurement. The Agreements are based on the principles of nondiscrimination among countries, national treatment, and transparency of trade rules and regulations. Some exceptions, however, such as preferential treatment for developing countries and regional and bilateral free trade agreements, are allowed.

The Doha Round

The Doha Development Agenda “round” of multilateral trade negotiations was launched in November 2001. The negotiations were characterized by persistent differences among the United States, the European Union (EU), and developing countries on major issues, such as agriculture, industrial tariffs and nontariff barriers, services, and trade remedies. For example, developing countries (including emerging economic powerhouses such as China, Brazil, and India) sought the reduction of agriculture tariffs and subsidies among developed countries, nonreciprocal market access for manufacturing sectors, and protection for their services industries. In contrast, the United States, the EU, and other developed countries sought reciprocal trade liberalization, especially commercially meaningful access to advanced developing countries’ industrial and services sectors, while retaining some measure of protection for their agricultural sectors. The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) entered into force on February 22, 2017, and may be the lasting legacy of the Doha Round. The TFA aims to remove customs obstacles at the border through commitments to facilitate and expedite the movement, release, and clearance of goods, including goods in transit.

WTO members were unable to announce major deliverables or multilateral negotiated outcomes at the 11th Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in December 2017, and continue to work toward consensus on future work plans. However, separate groups of WTO members announced multiple initiatives and committed to new work programs or open-ended plurilateral talks on e-commerce, investment facilitation, and micro and small- and mediumsized enterprises. The United States signed on to the declaration in support of e-commerce and the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) noted that “MC11 will be remembered as the moment when the impasse at the WTO was broken … like-minded WTO Members and their constituents are not held back by the few Members that are not ready to act.”

Agriculture and Development

While no breakthroughs were reached at the 2017 Ministerial, members committed to continue negotiations on fisheries subsidies, now with a goal of completion by the next Ministerial in June 2020. In the 2015 Ministerial, members agreed to a number of agriculture initiatives, including new disciplines on export financing and export state trading enterprises; to phase out export subsidies; and to minimize or eliminate the impacts of food aid on local commercial markets. None of the agriculture commitments are legally binding nor are they subject to dispute settlement. Members also reached agreement on several measures for least developed countries (LDCs), encompassing various special and differential treatment initiatives in the areas of preferential rules of origin; duty-free quota-free access for cotton; and exemptions from intellectual property rights (IPR) commitments for medicines until 2033.

Current Challenges

After 14 years of largely fruitless Doha negotiations, many intractable issues remain unresolved in the trading system. While developing countries remain focused squarely on agriculture, developed countries have linked ambition in agriculture to reciprocal ambition in industrial tariffs and services liberalization, especially for advanced emerging market economies. With the Doha Round over, some issues, ideally negotiated multilaterally, remain contentious. For example, new attempts to limit or discipline agricultural subsidies, address the special safeguard mechanism, or resolve concerns on public stockholding programs for food security may founder for want of a negotiating venue.

In addition, in the two decades since the WTO’s establishment, new barriers and other issues not considered in earlier rounds have emerged. Developed economies seek to incorporate new issues, such as digital trade (crossborder data flows, cybertheft, and trade secrets), stateowned enterprises, new nontariff barriers, global supply chains, and the relationship between trade and environment rules, that pose challenges to the trading system. The USTR has commented that the WTO is not designed to deal with the mercantilist and industrial policies of China. With clear disagreements at the conclusion of the 2017 Ministerial, there is debate about the future of the WTO as a viable and effective multilateral trade negotiating organization.

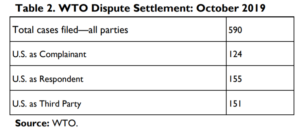

Dispute Settlement. To supporters, the dispute settlement (DS) system is considered one of the successes of the existing WTO system. However, some are concerned about the continued legitimacy of the DS system if no further WTO agreements are reached, thus preventing new trade issues from being adjudicated in the DS system.

The Trump Administration has highlighted perceived problems with the DS system. It has raised issues with what it considers overreach in WTO DS decisions, which may create new obligations not specifically negotiated in the Uruguay Rounds, especially in the area of trade remedies. Perhaps to encourage DS reform, the United States has blocked the appointment of new Appellate Body (AB) jurists, which has hampered the system’s ability to hear cases. The AB currently has three jurists (the minimum number to hear a case) out of seven positions. In December 2019, the terms of two of the three will expire, leaving the AB unable to function if no new jurists are appointed.

Unilateral Enforcement Action. Some members are challenging recent U.S. unilateral enforcement actions through the WTO DS system, but some observers express concern that U.S. tariffs imposed under Section 232 and Section 301 of U.S. law may undermine the credibility of the WTO system and its agreed-upon rules and could lead to tit-for-tat retaliation and/or trade war.

Bilateral, Regional, and Plurilateral Agreements. Outside the WTO, some members likely will continue to pursue sector-specific plurilateral deals or bilateral and regional trade agreements where progress can be made more readily by assembling coalitions of interested parties rather than in the consensus-driven WTO forum. However, countries or regions that do not participate may be marginalized from the trading system and face heightened trade restrictions from those within these agreements.

Other Initiatives

Aside from the agreements reached at ministerial meetings, several other initiatives are underway within and around the WTO. These include multiple plurilateral negotiations.

- As noted above, some WTO members agreed to establish negotiations on e-commerce at the 11th Ministerial. These talks among over 75 members representing 90% of global e-commerce trade launched in March 2019. The United States seeks a high ambition for these negotiations, including commitments on crossborder data flows, a ban on data localization, and disciplines against forced technology transfer. However, China’s proposal is for a more limited agreement.

- The revised plurilateral Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) provides market access for various nondefense government projects to its signatories. It entered into force in April 2014 and currently has 45 members, including the United States and EU.

- A subset of members agreed in 2015 to expand product coverage for tariff-free treatment in the 1996 Information Technology Agreement (ITA). The updated ITA will eliminate tariffs over seven years on 201 additional goods. Tariff reductions or elimination are applied on a most-favored-nation (MFN) basis to all WTO members. Countries began implementing tariff reductions per country-specific schedules in July 2016.

- The Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) negotiations, initiated by 14 members in July 2014, include the United States and China, representing 86% of global trade in such goods. Like ITA, the EGA would apply on an MFN basis to all WTO members. Despite 18 rounds of negotiations, the agreement is not concluded. Most parties blamed China for the stalemate, as it rejected the list of products to be included and requested several lengthy tariff phaseout periods which other countries refused to accept. The EGA’s future remains uncertain.

To read original report, click here