The IFPRI Food Security Portal’s Excessive Food Price Variability Early Warning System is showing excessive levels of price volatility in the four major food commodities: Wheat, maize, rice, and soybeans, as well as for cotton. Markets for hard and soft wheat and soybeans had already been more volatile than normal since late 2021, well ahead of Russia’s invasion in Ukraine, which began on Feb. 24. That conflict, coming on top of the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, has already contributed to spiking food prices, with possible major consequences for global food security.

Rising price volatility poses a distinct threat, as it induces greater market uncertainty, which affects production decisions, and can spur speculative behavior. Both would fan further food price inflation. What is driving the current price volatility, and what are its implications for markets and food security?

The dangers of high price volatility

Tracking food price volatility provides a temperature check on global food markets. When prices fluctuate, it is more difficult for farmers to make decisions about what to produce and how; businesses are more reluctant to invest in food and agriculture; and ultimately consumption decisions are affected through higher prices and/or lesser availability, particularly in rural areas that heavily depend on agriculture and among low-income households who spend most of their income on food.

Volatility was high during the 2007-2008 and 2010-2011 global food price crises. Prices of staple foods rose quickly, followed by a period of high price variability that created major uncertainty in food markets. The excessive price variability tool was developed precisely to provide early warnings of unusual price movements to market actors, including farmers, traders, investors, and policymakers.

The current situation compared to early pandemic period

Food prices were already high before the war. Poor harvests in South America, strong global demand, and pandemic-related supply chain issues had reduced grain and oilseed inventories and drove prices to their highest levels since 2011-2013. Prices of key energy-intensive inputs such as fertilizer were and continue to be at near-record levels. Then came the invasion, which is creating major market disruptions. Russia and Ukraine account for 30% of global wheat exports and supply millions of tons of wheat to food import-dependent developing countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. An ongoing war will certainly drive prices higher still and erode food security for hundreds of millions of people.

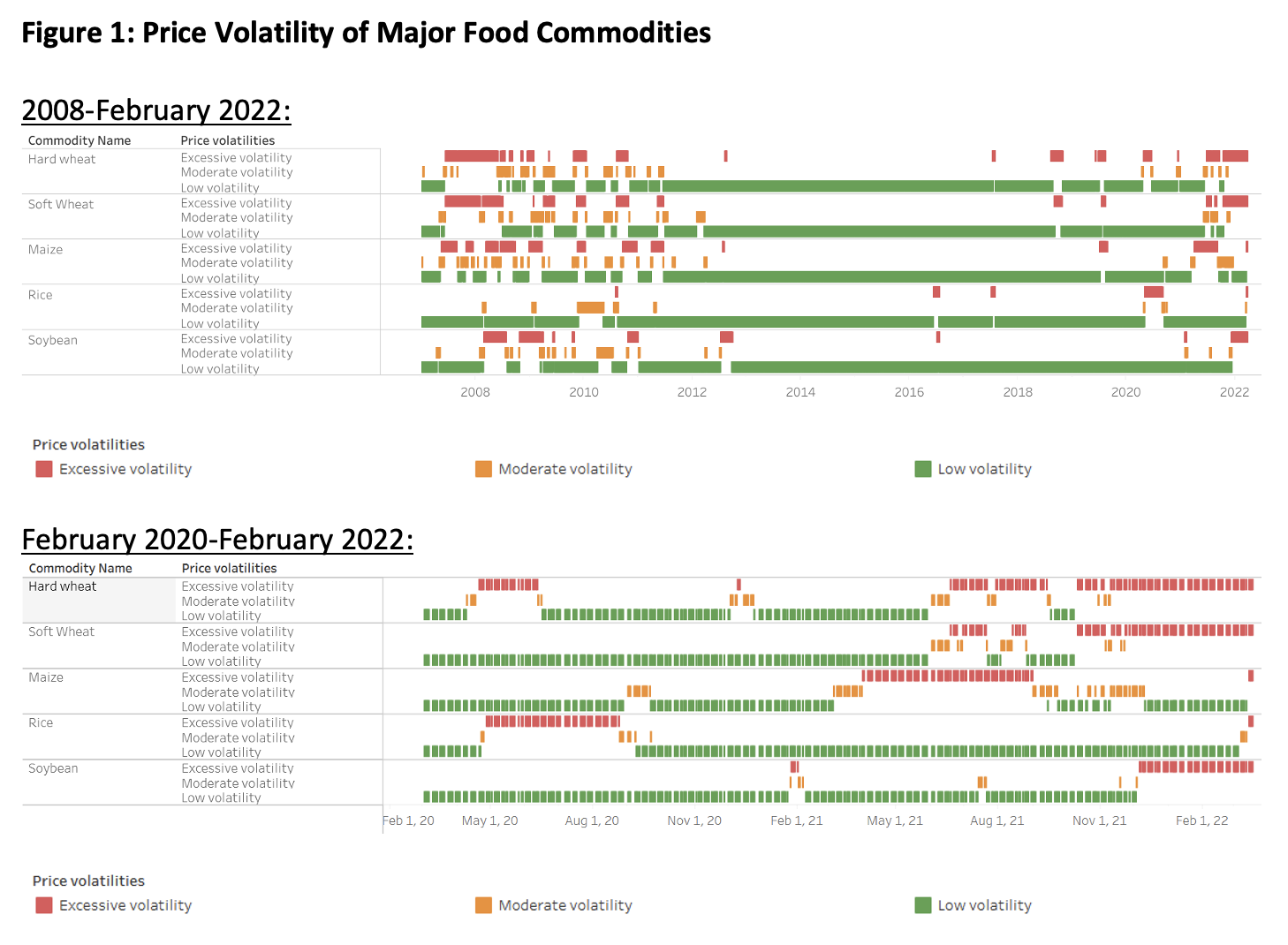

Looking back, most staple food prices also showed excessive volatility in the aftermath of the global food price and financial crises until 2012 (Figure 1). World market prices for basic staples were then calm for the most part until the recent rise in volatility.

Source: Excessive Food Price Variability Early Warning System, Food Security Portal, facilitated by IFPRI.

Among the major staples, prices of rice and wheat became very volatile following the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns, driven in part by export restrictions imposed by some major producing countries. Russia and Kazakhstan, for example, imposed export bans on wheat and Viet Nam imposed a short-lived ban on rice exports. In contrast to the 2007-08 global food price crisis, which led many countries to imposing prolonged trade restrictions, most of these more limited recent measures were retracted by mid-2020 and staple food markets returned to lower, “normal” levels of volatility. This period of relative calm lasted only through the first part of 2021, as the deepening of pandemic-related supply chain disruptions mixed with strong demand driven by the global economic recovery.

Price volatility has continued to intensify since reaching excessive levels for wheat, maize and soybeans in the final months of 2021. Markets for wheat and soybeans have remained volatile since, while that for maize returned temporarily to calmer waters. Following the invasion of Ukraine, however, maize prices again turned highly volatile, as did rice prices, so prices for all four staple foods are now in that state. Here is the situation for each:

- Wheat: Drought in many wheat-producing regions, including North America and the MENA region, and strong import demand from China, has created concerns over adequacy of supplies, while shipping disruptions and grain export policy in Russia pre-war added to the uncertainty in global wheat markets. The invasion has exacerbated supply concerns, intensifying price volatility.

- Maize: Conflict-related supply concerns have also stoked price volatility in global maize markets. Ukraine is the world’s fourth-largest maize exporter, and the war is putting the next harvest and the country’s capacity to export in jeopardy.

- Soybeans: Drought in Brazil and Paraguay sharply lowered production prospects for soybeans, driving price volatility starting late in 2021. Market dynamics of other major oilseeds have also contributed to soybean price volatility. Increasing concerns over palm oil supply—particularly due to damage caused by typhoon-related flooding in Malaysia—has led to increased demand and higher prices for soybean oil, a palm oil substitute for food and fuel. Similarly, the conflict in the Black Sea region, an area that accounts for well over half of the world’s supply of sunflower seed oil, has sent buyers scrambling for alternatives—also contributing to the excessive price volatility seen in soybean markets.

- Rice: The war has increased feed demand for rice on the heels of supply concerns in maize and wheat, pushing rice prices into excessive volatility territory.

The importance of monitoring food price volatility in the near term

Some conditions that contributed to price volatility following the initial COVID-19 lockdowns remain relevant now. Supply chain disruptions continue to be a factor, and tracking export restrictions is again important since such policies could lead food prices to spiral even higher.

One difference between the two periods is the scale of the disruptions in staple food markets. While the period of initial pandemic lockdowns saw some isolated volatility, the Russia-Ukraine war is affecting all major food staples. In addition, fertilizer prices are a greater factor now than at the beginning of the pandemic. Already at extremely high levels before the war began, fertilizer prices could continue rising as potash exports from major producer Belarus are cut off and Russia, another important fertilizer producer, is considering an export ban. High prices for natural gas, a feedstock for nitrogen-based fertilizers such as urea and ammonia, have boosted fertilizer prices as well.

Higher fertilizer prices could depress production, leading to less grain on the market in 2022 and putting further upward pressure on already-high food prices. With the conflict still unfolding and outcomes highly uncertain, monitoring food price volatility is more relevant now than at any time since the food price crises of 2007-08 and 2010-11—with the food security of millions at stake.

Brendan Rice is a research analyst in IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division where he works on the Food Security Portal.

Manuel Hernández and Joseph Glauber are MTID Senior Research Fellows

Rob Vos is the Director of the Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID) at IFPRI

To read the full commentary by the International Food Policy Research Institute, please click here.