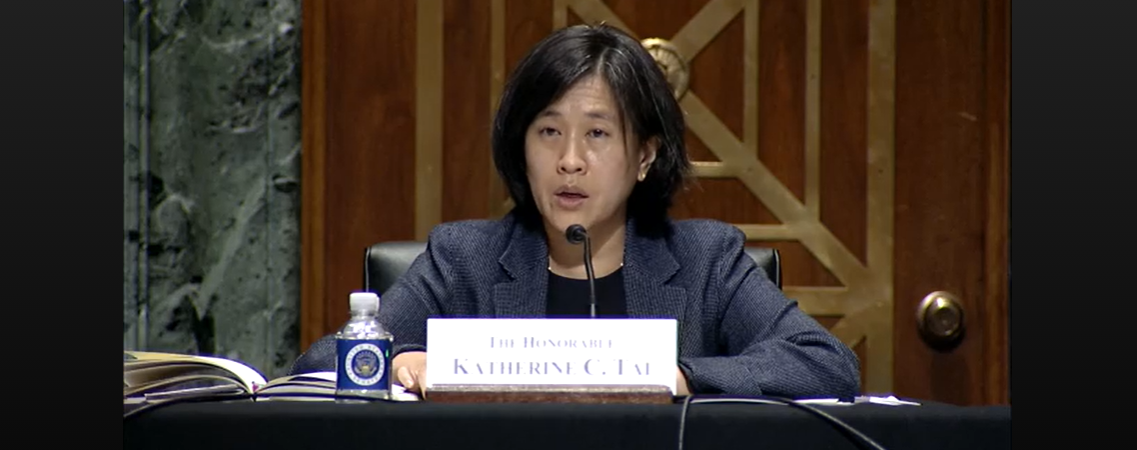

Ambassador Katherine Tai, the U.S. Trade Representative, recently testified to Congress that trade can be a force for good, by growing the middle class and addressing inequality, and that the U.S. is strongest when we work with our partners and allies around the world.

U.S. engagement in the Pacific is critical to this country’s workers, small businesses, values and economic and national security interests. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is an important initiative, recognizing the value of the U.S. as a standard-setter — for worker, environmental, digital and infrastructure standards — in order to continue as a 21st century global leader. This is especially important given China’s regional dominance. The IPEF’s goal of high labor and environment standards, as well as digital standards of democracy, transparency and accountability, are important counterparts to China’s model.

An important challenge facing the Biden administration is offering sufficient incentives for less-developed countries, especially ASEAN countries, to join the framework. The framework has four key pillars — infrastructure, supply chain resiliency, fair and resilient trade, and tax and anti-corruption. The first two pillars are the most attractive; they offer the potential for financing of infrastructure and sourcing of suppliers. The trade pillar is more challenging since it seeks to develop digital, labor and environmental standards. While the ASEAN countries welcome U.S. regional reengagement, setting these standards will require difficult domestic concessions from them. If the IPEF is to attract countries beyond Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore and South Korea, it must include strong incentives for countries to make these changes.

The U.S. has a limited range of incentives to offer countries to make difficult concessions. Lowering U.S. tariffs to offer increased access to the U.S. market is undoubtedly the best incentive. Although U.S. tariffs are generally low, tariffs are high in sectors such as agriculture or textiles, which are of particular interest to developing countries. When Vietnam wanted to gain access to lower duties on footwear and apparel by joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership, it pushed through significant domestic reforms. Tariff market access ultimately may be necessary to achieve the IPEF’s vision, and congressional passage may be necessary to assure countries that a future administration will not pull out of the framework.

For political reasons, however, this option is not on the table, so we must consider other incentives to encourage less-developed countries to join the trade pillar. Although the U.S. is not offering to lower its bound tariff rates, there are other ways it could increase access to the U.S. market. A number of Indo-Pacific countries still face Section 232 (national security) tariffs on steel and aluminum exports, imposed by President Trump in 2018. These tariffs should be eliminated for countries meeting certain standards in the IPEF trade pillar.

Secondly, while the U.S. isn’t offering to lower its tariffs, it can offer assurances that they won’t be raised — an important benefit during this time of increased protectionism. In a side letter to the United States.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the U.S. agreed to put in place guardrails for future Section 232 tariff increases and added a 60-day notice and consultation requirement before undertaking tariff measures. This reduces the likelihood of surprise tariffs and can help resolve crises before imposing trade barriers. The U.S. could incorporate similar provisions in the IPEF, perhaps expanding them to include other types of tariff measures, for countries that meet key standards. The U.S. should work cooperatively with countries regarding regulatory measures that facilitate those countries’ exports to the United States.

The U.S.could create a preferred supplier, or “trusted country,” status for countries meeting a certain level of labor, environmental and digital standards assurances — including ensuring that no forced labor is used throughout their supply chains. These countries could benefit from an expedited process through U.S. customs. (A similar program exists to expedite imports for companies who meet certain standards.) Advancing paperless trading by making e-versions of documents available, such as e-invoicing and digital rules of origin certificates, also could be part of the trusted country program. Countries that meet certain standards would be allowed to use electronic signatures and certificates to expedite product shipments.

The second category of incentives is providing capacity-building funding and technical assistance to countries to facilitate their reaching desired standards. For example, the U.S. offered Mexico $210 million to help raise its labor standards, as required under the USMCA.

In addition to government-funded capacity-building, the U.S. could create opportunities to partner with American companies in the region. This can take the form of investment projects or skills training. Many companies have programs that could be expanded upon, especially with government support.

For the best incentives, the U.S. should consider integrating the pillars, rather than asking countries to join each one individually. For example, the U.S. could use money allotted for the infrastructure pillar as a carrot to incentivize a country’s participation in the trade pillar. The infrastructure pillar also offers opportunities to leverage decarbonization and anti-corruption goals.

The supplier resiliency pillar can be tied to the trusted country program: Qualifying countries could gain advantages through this pillar. Such “friend-shoring” can be an important part of supplier resilience, especially when moving sourcing for key technologies out of China. This is a chance to rethink U.S. supply chains and to encourage sourcing from countries that advance labor rights, support decarbonization and adopt transparent, democratic digital standards.

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework provides an important opportunity for U.S. leadership in the region, including providing countries a values-driven alternative to China’s standards. America must make it attractive for developing countries to adopt higher labor, environmental and digital standards. Achieving this goal would produce an important result — for the U.S. and for businesses and workers in the Indo-Pacific.

Dr. Orit Frenkel is co-founder and CEO of the American Leadership Initiative. She is a former senior executive at the General Electric Company and served as director for trade in high-technology products at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

To read the full commentary by The Hill, please click here.