Background

- Since 1998, the WTO Members have applied a moratorium against tariffs on international electronic transmissions (commonly referred to as the WTO ‘E-Commerce’ Moratorium). However, some WTO Members have recently debated whether the moratorium remains in their economic interest, given the potential revenues that might be generated by imposing tariffs on electronic transmissions. The study examines the impact on India, Indonesia, South Africa and China (and the general case for developing countries) and concludes that imposing such tariffs would be fiscally counter-productive.

- Putting aside any legal questions, a country that opted out of the moratorium may apply tariffs affecting a wide range of cross-border business activities. Our research shows that if countries ceased to uphold the moratorium and levied import duties on digital goods and services, they would suffer negative economic consequences in the form of higher prices and reduced consumption, which would in turn slow GDP growth and shrink tax revenues. Yet our research indicates that the payoff in tariff revenues would ultimately be minimal relative to the scale of economic damage that would result from import duties on electronic transmissions.

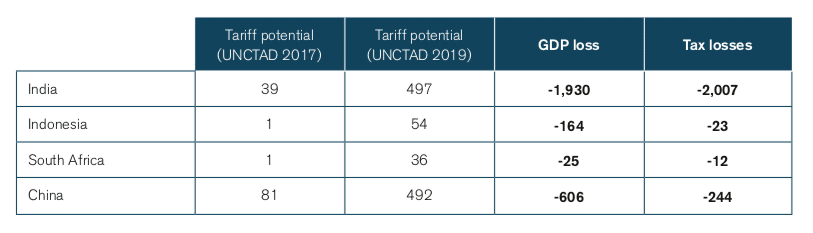

GDP and tax losses based on global imposition of tariffs on electronic transmissions (Scenario 2) on four economies. (in millions of US$) Impact on GDP and the economy

Impact on GDP and the economy

- Each of the four countries examined in our study would lose considerably more in gross domestic product (GDP) than they would gain in tariffs. Assuming a likely scenario in which tariffs imposed by one country gave way to widespread reciprocal tariffs (Scenario 2), India would lose 49 times more in GDP than it would generate in duty revenues. The figures are even more skewed for Indonesia, which would give up 160 times as much GDP as it would collect in tariffs, while South Africa would lose over 25 times more and China, seven times more.

Impact on tax revenues

- Likewise, if the goal is to fill tax coffers, imposing tariffs is a wrong-headed strategy. Duties would take a toll on domestic output that would depress tax collection. The net result for tax authorities is strongly negative. Again assuming a situation of reciprocal tariffs (Scenario 2), the loss of tax revenues is estimated to be 51 times larger than the tariff revenues for India, 23 times for Indonesia, 12 times for South Africa and three times for China. In short, a tariff on electronic transmissions would prove to be a highly inefficient form of tax collection.

Conclusion from the results

- In assessing existing literature on this issue, our study examined the potential tariff revenue losses projected in 2017 and 2019 UNCTAD reports that made a case for ending the moratorium. However, UNCTAD research did not discuss the economic and domestic tax losses that are likely to ensue if duties are implemented – and which we detail further in our own study. UNCTAD reports also did not take into account the significant enforcement and compliance costs involved in implementing electronic tariffs.

- In addition, UNCTADs’ research was based on certain assumptions that we believe merit serious scepticism – including that in the future, virtually all physical media or paper-based products would be digitised and therefore exempt from duties under the moratorium. Finally, those reports substantially overstated the potential of ‘lost’ tariffs due to digitalisation by over-estimating the value of digital trade – despite contrary evidence that the price of digitally-delivered items has tended to decline over time.

- Both UNCTAD reports have sought to argue that the adoption of 3D printing or additive manufacturing would make it harder for developing countries to capture taxes on manufactured goods. We believe the premise of this argument is questionable. It remains the case that, even if the files for 3D manufacturing (e.g. schematics and blueprints) can only be taxed once, the source materials used to manufacture products (the additives, or the thermoplastic ‘ink’ of a 3D printer) will remain subject to tariffs and sales tax. The more items are manufactured, the more states would stand to collect in tariffs and sales tax on 3D ‘ink.’ In short, we see no reason that the advent of 3D printing would undermine the economic logic of maintaining the moratorium.

- Finally, we would draw attention to one of the less-heralded benefits of digital trade, and one that is a boon to tax collection e-commerce forces more transactions into a transparent, trackable and therefore taxable realm. For many developing countries, where tax evasion is a constant challenge, a shift towards digital transactions is likely to help boost domestic tax collection. Far from undermining government sources of revenue, the growth of e-commerce stands to enhance a nation’s tax base, pushing grey market transactions into a taxable space.

Introduction

Since the 1998 Geneva Ministerial Conference, the WTO Members have upheld a moratorium against tariffs on electronic transmissions that has been extended every two years at each WTO Ministerial. While many bilateral and regional trade agreements have made the moratorium permanent,[1] several WTO Members have recently voiced concerns that the moratorium may result in a loss of potential tariff revenues.

As our research makes clear, however, countries gain far more through the moratorium in terms of broader economic benefits than they would give up in tariff collections. Our study, a comprehensive assessment of the impact of electronic transmissions, bears out the well-known axiom of trade economics that tariffs often end up causing losses inside the economy that are larger than the revenue they generate at the border: indeed, it is well documented that tariffs distort the economy, increase domestic prices, reduce productivity and end up reducing government income from other taxes.[2]

We take a comprehensive approach in calculating the net impact of tariffs, considering how reduced economic growth would affect consumption, corporate and personal income taxes. The results are striking: in one scenario involving India, we find that the moratorium serves to prevent tax erosion of as much as $2 billion.

In fact, the economic losses cited in this study are likely to be understated since this study does not take into account enforcement costs – i.e., that existing customs infrastructure is only designed to collect duties on traditional goods and not services or intangibles. The compliance costs associated with implementing e-commerce tariffs would likely further reduce projected tariff revenues.

In explaining our conclusions, we allude to two studies that have been cited by WTO members sceptical of the value of the moratorium. The studies, both published by UNCTAD (in 2017 and 2019),[3] have advocated for an end to the WTO ‘E-Commerce’ Moratorium. Their authors argue that as increasing volumes of electronic transmissions replace trade in physical goods, countries are losing out in the form of foregone tariffs. The UNCTAD reports suggest that a tariff on electronic transmissions could recoup these lost tariffs.

As we explain below, this perspective ignores the substantial benefits that accrue to national economies from keeping electronic transmissions duty-free, particularly in terms of economic growth (though there is a substantial consumer benefit). As we will argue, the benefits of maintaining duty-free status are far greater than the potential revenues that could be generated through tariffs.

[1] Notably CPTPP, USMCA and EU bilateral agreements have incorporated the WTO ‘E-commerce’ Moratorium without sunset clauses.

[2] See inter alia Why tariffs are bad taxes, the Economist, July 31, 2018.

[3] UNCTAD, Rising Product Digitalisation and Losing Trade Competitiveness, 2017; Growing Trade in Electronic Transmissions: Implications for the South, 2019.

The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this study from the members of the Global Services Coalition.

ECI_19_PolicyBrief_3_2019_LY04To access original source, click here